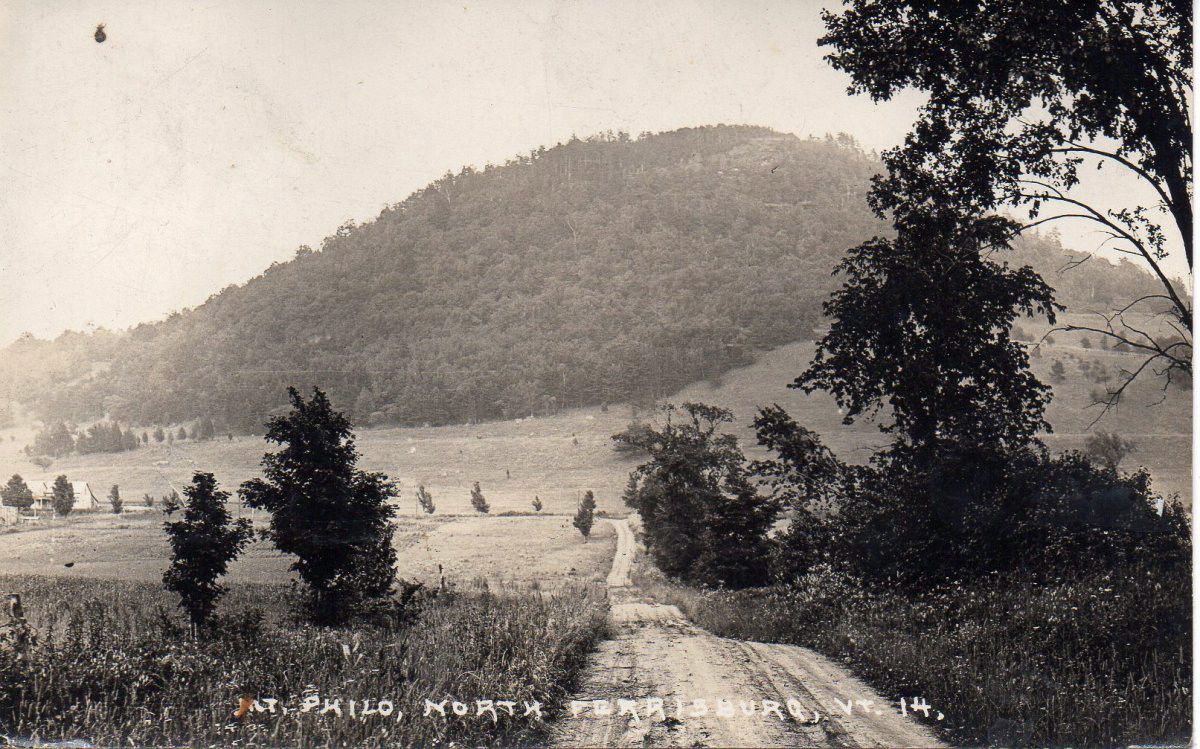

Local resident Judy Chaves began writing a book based on her research into her daily hike up Mt. Philo. Secrets of Mount Philo: A Guide to the History of Vermont's First State Park, published in 2018 by the Vermont Historical Society, is a fascinating trip through the mountain's intricate past and a guide to its relics, hidden byways and natural communities.

Mount Philo emerged millions of years ago in the mists of geologic time. Scientists call it a klippe, a relic of the Champlain Valley thrust fault. Such a fault appears when one immense plate of the Earth's crust is forced up over another. The formation of the Champlain Valley thrust fault, which occurred roughly 500 million years ago, is one of the mega-events that shaped the Champlain Valley. Philo, like Snake Mountain off to the southwest and other rocky eminences rising above the valley, is an eroded remnant of the leading edge of that thrust.

Ever since humans came along, hundreds of millions of years later, Philo's summit has provided visitors with an unparalleled vista of the Champlain Valley, Lake Champlain and the Adirondack Mountains across the lake in New York. There's no evidence that Native Americans lived on the mountain, but they may have used it as a strategic lookout.

Nobody knows for sure how Mount Philo got its name. The most likely explanation, Chaves believes, can be found in Esther Munroe Swift's classic book Vermont Place Names: Footprints of History, which says it was probably named during one of New England's "bursts of enthusiasm for names with a classical flavor." Philo means "love" in Greek.

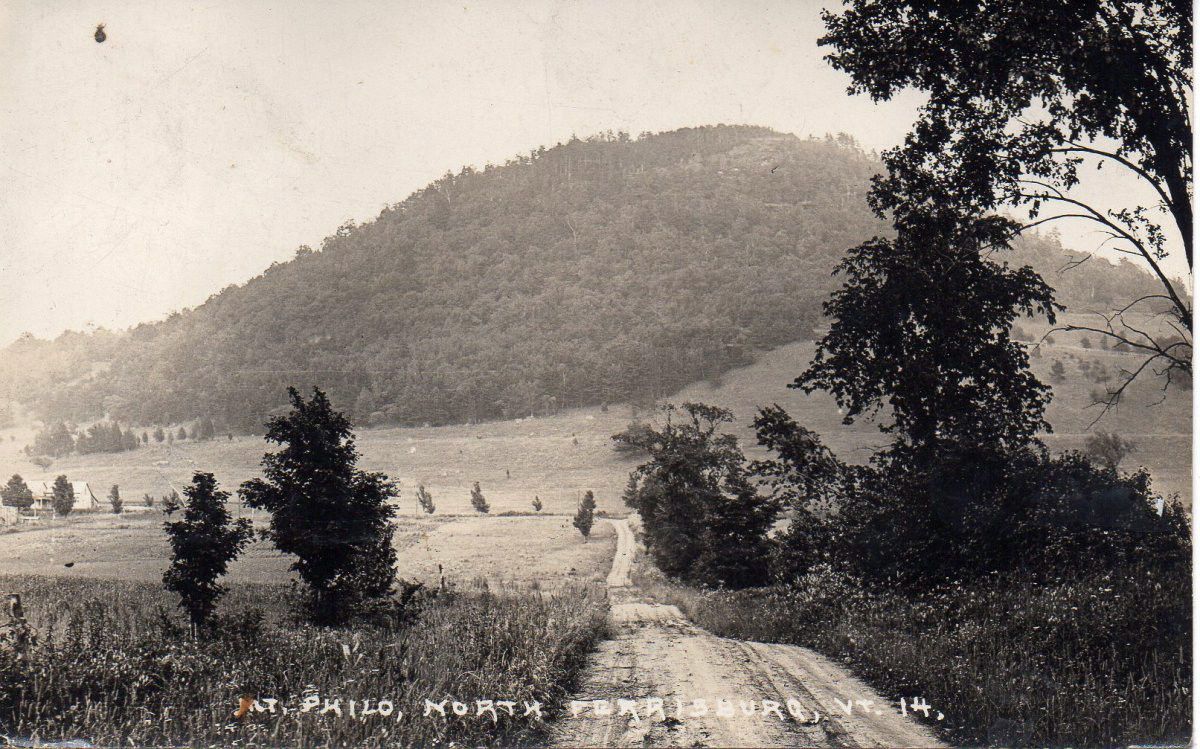

As European settlers moved into Vermont, farms began to surround Mount Philo. And as the nation's demand for wool grew, nearby sheep farming burgeoned. By the middle of the 19th century, the mountain was completely denuded of its primeval forest cover.

That was the story throughout Vermont. In the 1840s, Chaves' book and other historical references point out, nearly 1.7 million sheep inhabited the state, and farmers had cleared three-fourths of its trees. But after the Civil War, the demand for wool declined, the Midwest opened — with its flat, fertile, more temperate lands that could produce meat and wool more efficiently — and sheep farming moved west.

Dairy cows took the place of sheep and soon dominated Vermont agriculture. Since cows don't climb mountains, the lower slopes of Mount Philo remained pasture, but forests returned to its rocky upper half.

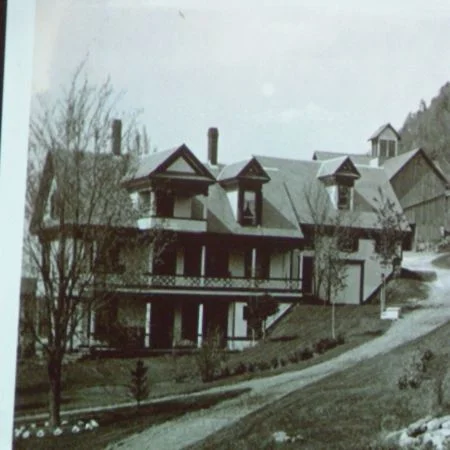

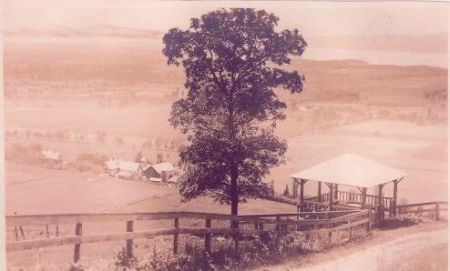

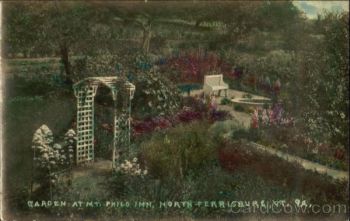

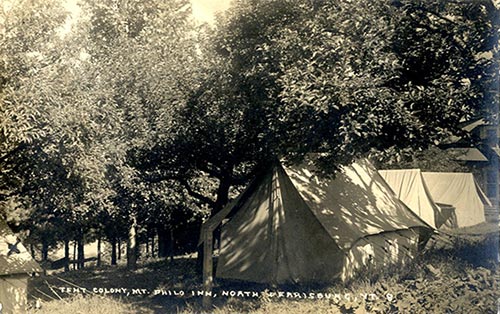

Then, as now, making money from a farm was difficult, and many Vermont farmers began taking in city tourists to supplement their income. It was, in effect, an early form of agritourism. In 1886, Frank and Clara Lewis bought a farm about a quarter mile south of Mount Philo and started welcoming tourists from New York City and Boston. Their business prospered, and they replaced the original farmhouse with a larger, more comfortable building they named Mount Philo Inn.

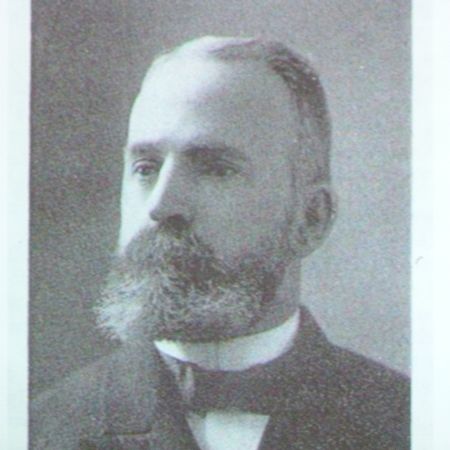

At that point, fate stepped in. A wealthy Massachusetts couple, James and Frances Humphreys, came to stay at the inn, fell in love with the place and began summering there. They regularly trekked up the adjacent mountain.

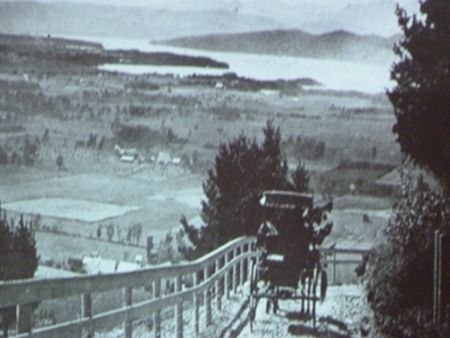

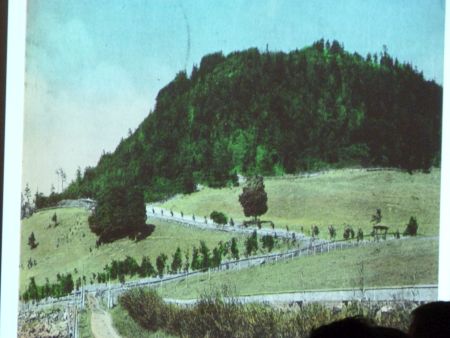

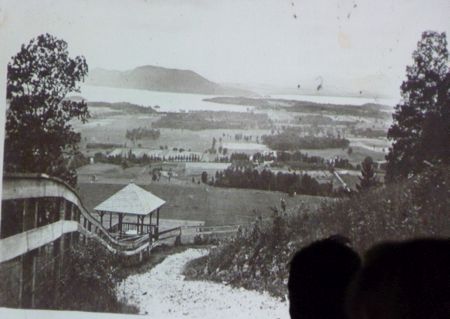

At about the same time, carriage roads were becoming fashionable on mountains throughout the Northeast, giving visitors an elegant and less sweaty alternative to hiking uphill. In 1901, Frank Lewis began constructing a carriage road on Philo. Along the roadway he built gazebos, rest stops, a springhouse and other amenities. Eventually, Lewis built a 50-foot wooden tower on the summit that offered a 360-degree view. (Later, steel towers replaced the wooden one. None remain today.)

As Chaves points out in her book, similar construction was going on all over the region. Carriage roads wound their way up Snake Mountain, Camel's Hump, Mount Mansfield, Mount Equinox and the White Mountains of New Hampshire. If you had a mountain — even a small one — you wanted a carriage road on it so your guests could navigate it in style.

By 1902, Mount Philo was a fully equipped tourist attraction, and Lewis promoted it in exuberant prose. A pamphlet declared: "The mountain road, threading its way through open fields and woods, affords a variety and intensity of scenic beauty seldom equaled in New England."

James and Frances Humphreys were his most enthusiastic guests. The couple bought land for a summer home near the mountain and eventually came to own the peak itself. Even after James died, in 1914, Frances continued to come to Vermont and was deeply devoted to Mount Philo. She wrote touching, sentimental verse about it.

When someone asked Frances whether she would have the mountain timbered, she insisted she would not cut a single stick. "There is something in the world besides money," she said.

Inn guests James and Frances Humphreys, of Dorchester, Massachusetts, first came in 1900 and grew so enamored of the place that they began buying much of the farmland on the mountain, built a summer home at its base, and urged the Lewises to build a carriage road for guests. In 1902, the road was complete, as were roadside gazebos, foot trails, benches, overlooks, and a summit observation tower. “The mountain road,” reads the inn brochure, “threading its way through open fields and woods affords a variety and intensity of scenic beauty seldom equaled in New England.”

The mountain, which 50 years prior had been cleared of trees and grazed by sheep, was now pasture on much of its lower half and forest on its upper: the epitome of the bucolic landscape being encouraged statewide as a lure for tourists. While other northern states were wooing urban vacationers with rugged wilderness, Vermont was offering the pastoral life, with easy access to nature. “Everything possible is done to make the way safe as well as agreeable,” Bassett quotes James Humphreys as saying about the carriage road. “All precipitous places are boarded by neatly painted iron railings, and at short intervals resting places are provided.”